Get the latest insights, product updates, and news from Permission — shaping the future of user-owned data and AI innovation.

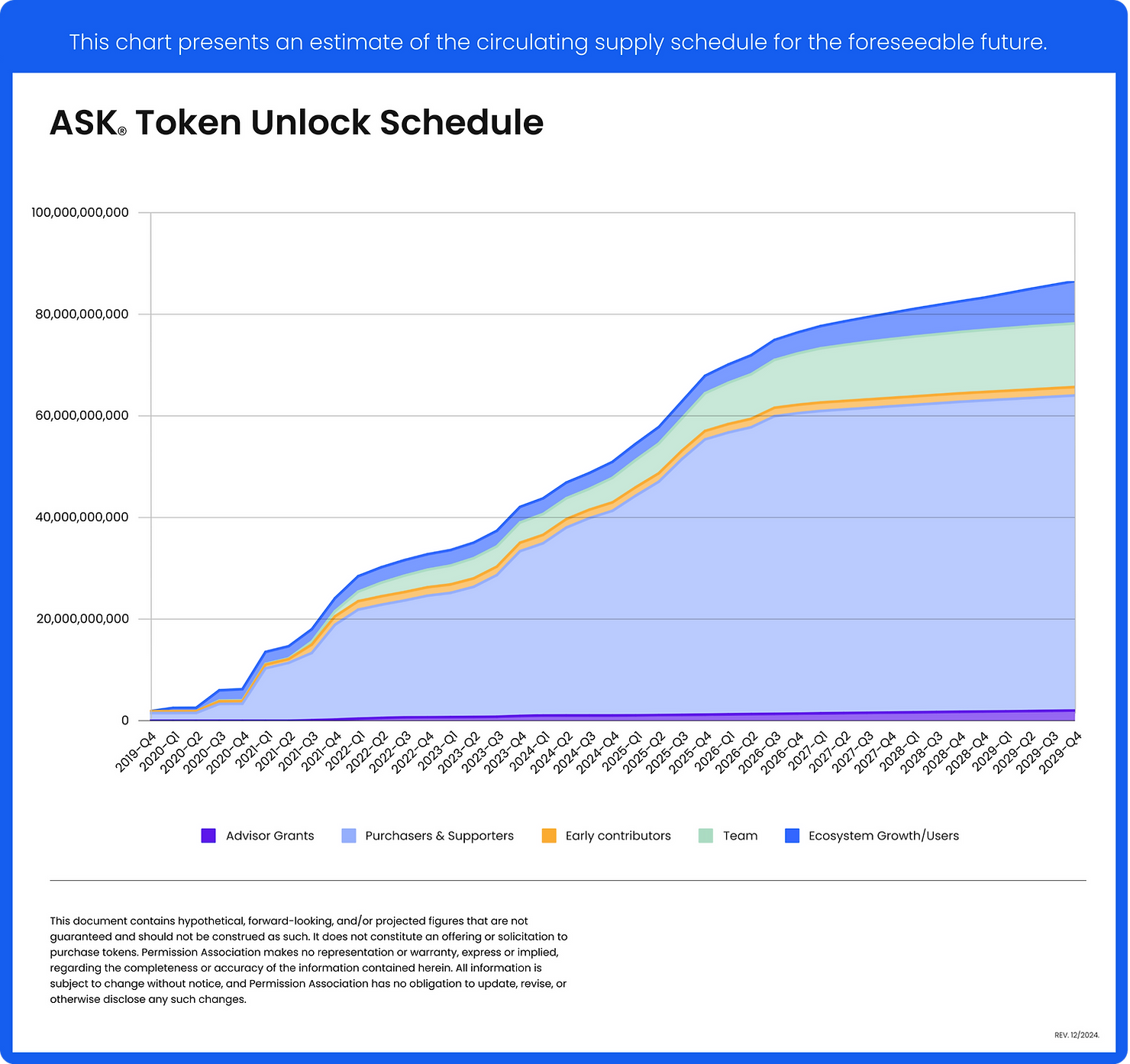

In the interest of transparency and open communication about the tokenomics that govern the Permission Protocol and how the supply of ASK is being managed, below is our planned sequence of token distributions set to occur over ten years from ASK’s original launch date. In our ever-evolving community, trust is paramount, and we want to ensure that there is absolute clarity regarding our current and projected circulating supply.

Total Supply and Circulating Supply

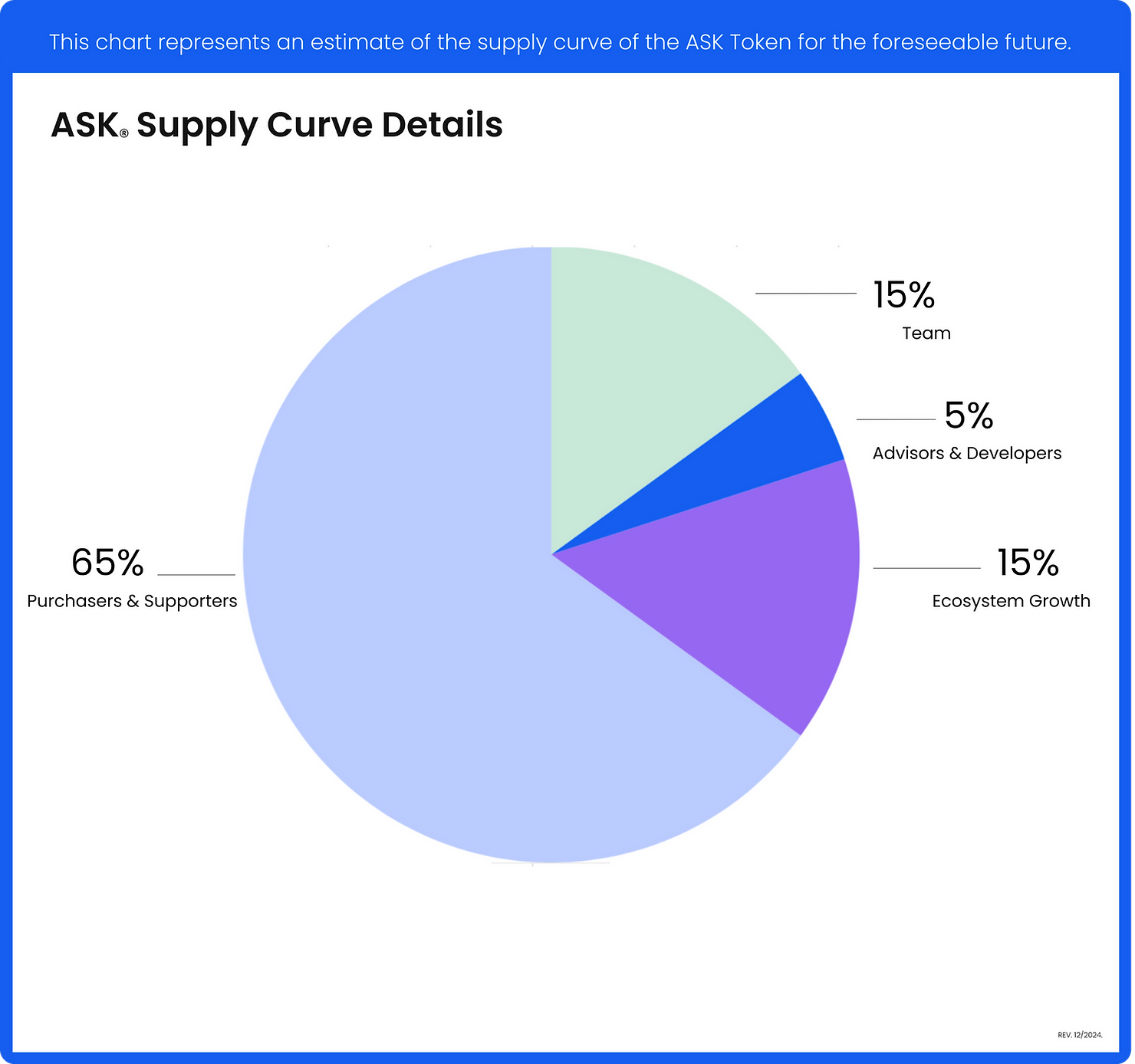

The uninflatable, unalterable total supply of ASK tokens stands at a substantial 100 billion. Of this allocation, 15% is earmarked for ecosystem growth, 65% is dedicated to Purchasers and Supporters, 5% is reserved for developer incentives and advisors, and the remaining 15% is designated for the core team. This extensive supply is intended to foster global adoption while ensuring that transactions are conducted in complete ASK tokens rather than fractional percentages.

Token Unlock Schedule

The below schedule is subject to adjustments to ensure a stable tokenomics model that supports Permission network’s health.

To view the circulating supply in real time via the following API endpoints, paste the below links into your browser:

https://api.permission.io/v1/token/supply?q=total

https://api.permission.io/v1/token/supply?q=circulating

Here’s a closer look at the circulating supply:

Two billion tokens are allocated to Series B-1 investors and the team. While these tokens have been unlocked, several of our dedicated investors are demonstrating their long-term support by refraining from releasing these tokens into the market for additional years.

Virtually all employees, board members, advisors, and a significant portion of our Purchasers and Supporters are subjected to multi-year lockup periods from the primary listing date. Indeed, all current team members are subject to a five-year vesting schedule that entails both a service and liquidity requirement. The Token Unlock schedule reflects tokens that will have met the service requirement only; in other words, team tokens will not vest and become available for distribution unless the liquidity requirement is also met.

Original team members and “seed token” holders, including our founder and CEO, Charlie Silver, are fully vested, but have agreed to adhere to additional lockup periods from the primary listing date. Even when fully vested, former employees and “seed” token holders are restricted to transferring or selling no more than 25% of their total vested and unlocked tokens per quarter.

Notably, no current team members, including the CEO, have executed any token sales to date. Moreover, it’s crucial to emphasize that only 72% of tokens reserved for current or former team members have been allocated. We reserve a substantial percentage for future employees, given the continuous growth of our team.

This lock-up schedule underscores our unwavering commitment to the long-term integrity of ASK. As a mission-driven, enduring project, we firmly believe this is the ethical path forward. Our founder, board members, advisors, and entire team share a profound belief in our mission, underlining our determination to develop the ASK ecosystem over an extended timeframe.

SAFT Holders (Early Contributors)

Regarding SAFT holders, the majority were entitled to access half of their tokens upon Mainnet Launch, with the remainder unlocking six months post-launch. Many of our most substantial SAFT holders have already taken custody of their tokens, while others have graciously agreed to extend their lock-up periods to one or more years from the primary listing date.

We constantly explore opportunities to encourage token holders to support us for the long term. Consequently, certain SAFT holders, Purchasers, and Supporters have agreed to extend their lock-ups to ensure that their tokens do not enter the circulating supply until later dates.

Updates

We remain committed to providing regular updates regarding the ASK supply. For those keen on understanding our projected supply increase, please refer to the “Permission Token Economics” section in our white paper, which elucidates how we’ve modeled user acquisition campaigns and a multitude of partnerships that will influence supply. Additionally, keep an eye on CoinMarketcap and CoinGecko for real-time updates.

At Permission, every aspect of our ecosystem, from total supply to circulating supply, and from release schedules to lock-up provisions, has been thoughtfully designed with our users in mind. Our mission revolves around growing the network through user incentives and expanding the number of Purchasers and Supporters to fuel the growth of our platform.

As one of the pioneers of a fair and trustworthy internet, you can rely on us to maintain our unwavering commitment to transparency. We are always prepared to present with utmost transparency how our model functions and how it is designed, ensuring that you, our community, remain well-informed.

Explore the Permission Platform

Unlock the value of your online experience.

%20(1).png)