Resources

Insights on building trusted, permissioned, and compliant data systems for the AI era.

Recent Articles

Permission Becomes Founding Member of Data Privacy Protocol Alliance (DPPA)

Permission is proud to announce that it is a founding member of the Data Privacy Protocol Alliance (DPPA) alongside BIGtoken, CasperLabs, Own Your Data Foundation, SQream, First Rate, Tapmydata, and more.

The DPPA is a group of organizations that have banded together to build a new decentralized data ecosystem that puts consumers in control of their data and competes against the entrenched data monopolies.

Ownership of our personal data will be a fundamental cornerstone of a future where data is owned by the individual and data monetization is possible. Together, we are collaborating to define universal standards of data usage, privacy and implement a decentralized data privacy blockchain that can ensure adherence to the policies set.

“Our data is still held captive and by an oligopoly of tech giants that rule over the data economy,” expressed Charlie Silver, CEO of Permission.io. “Partnering together with other companies that believe in the same values is the best way to return Data Ownership to the individual and move into the Web3 era.”

The entire Permission team is thankful to the leaders at BIGtoken and CasperLabs for spearheading this effort, which has allowed our like-minded companies to rally around a single cause. We believe that when individuals are given tools that empower them to individually choose how their data is shared and monetized, data privacy becomes a non-issue and justice prevails.

For more information, please visit the Data Privacy Protocol Alliance (DPPA) website.

Third Party Data: What Is It and Should You Use It?

Mismatches between advertisements and the people receiving them have been the bane of existence for both advertisers and consumers since — well, advertising became commonplace. And even the best-matched advertisements can fall flat due to poor timing, bad execution, ad fatigue, and numerous other reasons.

Fixing interruptive, ineffective ads once and for all while protecting user data privacy is what we’re doing right now, but in the meantime, where does third party data fit into the ad ecosystem? Third party data is both an attempt to solve personalization issues and also a creator of them.

But, before we go too far into the world of third party data and how businesses should approach it, let’s take a second to define the other three major types of data businesses use:

- Zero party data is any user data that is given up voluntarily by a consumer to a business or entity in return for some sort of benefit.

- First party data is user data collected by companies directly from their own customers like email addresses, phone numbers, and purchase behavior data.

- Second party data is first party data sold or given to another business.

What Is Third Party Data?

Third party data is any data collected and used by companies who have no direct connection to the users whatsoever. Examples include past purchases and demographic identifiers which are packaged and sold to businesses through various data marketplaces.

Third party data is collected from a wide variety of sources, refined into sellable segments by publishers or data management companies, and then used by advertisers to combine with their own first party data to reach and learn about new audiences at scale.

Third party data is packaged by these data managers into customer personas or other simple identifiers. If you’ve been to sites that allow you to target “college students” or “real estate agents,” then these sets are likely some form of third party data.

Data Sets Built From Our Digital Footprints

While third party data can include offline data like offline purchase behavior and store visits, third party data became the mammoth it is today after the invention of the internet, and more specifically, the invention of website cookies and mobile advertising IDs.

Every user performing almost any action online is leaving footprints — sort of like little cookie trails. If you think of these cookies as lego pieces, then third party data aggregators collect as many of these blocks from as many viable sources as possible and build them into customer segments, profiles, and opportunities for advertisers to use.

These lego structures (collections of cookies and data) can be sold in private or public marketplaces, where publishers (the people providing ad space) and advertisers can place restrictions and quality control measures to ensure their data isn’t being stolen and is compliant with new privacy laws like GDPR, the CCPA, and the CPRA.

There are many ways businesses use third party data, but two of the most common ways are bolstering their own first party data profiles and exploring new audiences.

Who Uses Third Party Data?

Any business who wants to improve their existing advertising targeting or discover more about their target market for any reason you can imagine. This effort is usually spearheaded by marketing, sales, and data departments.

How Does Third Party Data Work in Practice?

So how does the third party data ecosystem function? At its core, there are few major players:

- Demand-side platforms (DSPs)

- Data management platforms (DMPs)

- Supply-side platforms (SSPs)

Demand-side platforms like Google Ads let advertisers purchase ad space, supply-side platforms allow publishers (like websites) to sell ad space to advertisers, and data management platforms organize, collect, and package the data that DSPs and SSPs use.

Third party data is threaded through all of these platforms, but they are all aimed at doing the same thing: facilitating efficient advertising from companies to potential consumers. This is made possible by integrations and partnerships between these platforms, the providers of that data, and the aggregators of that data. Some platforms prioritize publishers, others prioritize advertisers, etc.

In the first wave of digital advertising, DSPs were where most third party data lived, but SSPs have been picking up more of the share in recent years due to ad inventory being more transparent.

A Real-World Use of Third Party Data

Let’s look at an actual use case for third party data.

Let’s say you (the user) went to Zillow.com and checked out houses and then went to 4-5 different blogs about home ownership and home buying. Based on this information, you may be tagged and placed into a data set called “potential home buyers,” which then a company like Rocket Mortgage could buy.

Rocket Mortgage could take that data and combine it with their internal data sets. They may have had a tag on you showing that you had read one of their blogs, but perhaps they didn’t know that you were also between 35-44 and married.

They can take that info, create a more complete picture of you, and then use that as a creative starting point to make more specific advertisements to you and others like you via social ads, TV placements, or any other ad channels made available by the data set.

The accuracy of that data will depend on the purity of the ad sets Rocket Mortgage purchased, and that’s what makes the entire ecosystem even more complicated. There are layers of private and public platforms from which to purchase third party data that have varying degrees of quality control and audiences available.

The Power of Third Party Data: How Businesses Use It

There’s no end to the ways businesses can use third party data, but generally speaking, third party data allows them:

1. To Deliver Personalized Ads at Scale

The more accurate a segment is, the more personalized advertising can be. This is the key appeal for all data in the marketer’s mind — the chance to say something to the right person at the right time to spur action.

Third party data and its large and dense data sets, in effect, hand what is unique about individuals to marketers en masse. Advertisers then take these insights and use them to educate their campaigns.

2. To Mine for New Audiences

Third party data is also useful for mimicking existing audiences — i.e. create a lookalike. If you know that your top customers are 18-24 and play college baseball, what could you do with the chance to reach 100,000 more of them?

3. To Enrich Existing Customer Profiles and Segments

Third party data is most effective when used in tandem with first party data. The combination of data you can trust with larger sets is one of the best paths to personalization.

4. To Optimize Product Experiences

Third party data can be useful when examining user behavior at scale. If you discover that your target demographic prefers video content to text, then that can change your entire marketing approach to that segment.

Third party data also helps companies understand how their potential and existing customers behave, which they can then use to shape their core offerings and services. For example, data scientists could mine third party data to understand how best to build an app’s UI (user interface).

The Most Popular Third Party Data Sources and Providers

Third party data is used all over the advertising world on different platforms. Some are DSPs, some are SSPs, and your choice in platform will depend on the data they have available, what advertising opportunities are made available, and the type of business you are.

Here are a few major examples of third party marketplaces or platforms that use third party data:

- Nielsen

- Lotame

- Social platforms like Facebook, Google, Pinterest, and TikTok

- Public government survey data

- Acxiom

- Mobilewalla

- Adobe

The Downsides of Third Party Data

While third party data can sound exciting to advertisers and publishers, there are many issues to be aware of. Here’s what to keep in mind when approaching third party data:

You could be using data that isn’t compliant with GDPR, CCPA, or CPRA.

Data privacy laws like GDPR hold businesses responsible for their entire data apparatus — not just what they have direct control over. In other words, businesses can be held responsible for data violations that occur via any partnerships or integrations.

If you plan on using third party data, you need to ensure that the data you purchase was gathered with express consent for the purpose it is being used and that the company you are working with isn’t violating any existing laws.

Cookies are on the way out, and this will hamstring a lot of third party data collection efforts.

Google, Safari, and Firefox have all vowed or already started to leave cookies in the past[*]. While this won’t destroy third party data — there are still a wide variety of ways you can collect and sell it, it will (at least temporarily) affect data availability and integrity.

Companies like Google do have other solutions in the works that are less invasive than cookies but still allow for effective targeting[*].

Juggling a lot of data sources can be difficult.

Third party data, especially at scale, requires consistent technical labor to utilize efficiently. While the marketplace is making it easier and easier for businesses to take advantage of third party data, there is almost always technical work involved when combining data sets.

Accuracy is often overestimated and ill-defined.

Not all third party data is gathered equally, which is another reason why taking the time to vet your provider is important.

For example, if you were a wedding website company, and you bought a packaged audience of people who are newly engaged or in long-term relationships, poor data management could mean that people in that audience are stale and have already gotten married, making your advertising irrelevant and a waste of money.

Your competitors could be using the same data.

Since third party data is packaged and sold, there is no guarantee that your competitors aren’t using the same data to target customers.

That doesn’t mean you can’t do a better job with messaging and product-market fit, but it is something to keep in mind.

Third Party Data: An Advertising Practice in Decline

While third party data is still a widely used and important resource for businesses, especially at the enterprise level, it is clear that many forces at work will diminish its effectiveness — and for good reason.

User data should be owned by the users themselves, not the companies they interact with online.

If we accept this, then the existing ecosystem that promotes company welfare over user privacy is fundamentally broken, and products that exist due to the exploitation of user data (like many third party data marketplaces and products), need to be sacrificed and adjusted to create a better, safer, and more democratized internet.

In other words, we need to discard the old internet advertising model and give users back ownership of their data while setting up opt-in advertising mechanisms that compensate users for their data. If this sounds impossible, it isn’t.

By using the capabilities blockchain makes available to us, we can reward users for interactions they have with advertisers of their choice. This approach will revolutionize the data-dependent advertising marketplace by prioritizing zero party data, which gives businesses better targeting/ROI and enables consumers to receive compensation for their data and engagement and receive ads that are more relevant

Think that sort of advertising model isn’t possible? Think again.

See how Permission is building that world right now.

What Is IDFA and Why Did Marketing Just Get More Difficult?

If you work with Facebook advertising or mobile apps in any capacity, chances are you’ve been sent a litany of updates about the infamous iOS 14.5 update. The marketing and advertising world is panicking, and it’s hard to argue that they’re overreacting.

The changes iOS 14.5 will make to the ad ecosystem and IDFA tracking is significant. They will hamstring conversion tracking, especially while everyone adjusts, and set the stage for even more restrictions on digital advertising moving forward.

We’re going to give you a brief overview of what IDFA is and how it’s been used in the past, and then we’ll dive into the topic of the day: how iOS 14.5 is changing the value of IDFAs and what you can do to keep your marketing ROI as high as possible.

What Is IDFA?

IDFA stands for IDentifiers For Advertisers, and they’re the equivalent of browser cookies for mobile phones.

Every single Apple phone ever made has a unique code attached to that device. No two are the same, and Apple, app developers, and the advertising world use these unique identifiers to track behavior within apps and pass that information on to different sources. Google also has their own version of this, known as GPS ADIDs.

To put it in context, if you serve up a Facebook app install ad to a new audience and 50 of them click through and download the app, Facebook uses the relevant IDFAs to match that click-through on their platform to the install event in the app.

This type of tracking has been digital advertising’s bedrock. IDFAs are used in everything: user tracking, measuring ROI, attribution, ad targeting, monetization, device graphs and insights, effective retargeting, programmatic advertising on DSPs and SSPs — you name it.

So when a company like Apple starts poking at that foundation, it makes sense why people are nervous.

Let’s talk about what Apple is up to.

The Current Buzz Over iOS 14.5 and IDFA

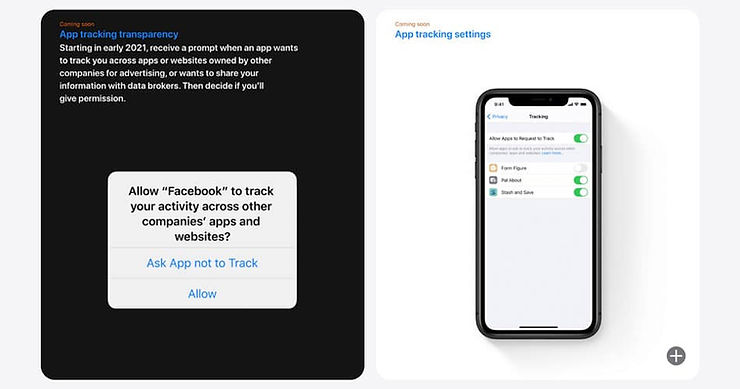

Last summer, Apple dropped a bombshell: their upcoming operating system update, iOS 14, would make the user default to allow companies to use a device’s IDFA to opt-in instead of opt-out.

This means any time a user downloads a new app, the developer must ask for consent before collecting any IDFA information. This is what that looks like:

If everyone clicked “Allow”, then advertising would continue like normal, but that’s not what people do. 31.5% of iOS users before this update were already limiting ad tracking[*], and while we don’t have numbers yet, there is no doubt that the percent of people who opt out will significantly increase.

So for every person who opts out, that’s another user who is more difficult to track, meaning advertisers will be working with less accurate data than before.

(Want to opt-out of IDFA tracking? On your iPhone or iPad go to Settings > Privacy > Advertising and then turn “Limit Ad Tracking” on).

Why Would Apple Make These Changes?

If things like Apple advertising and the mobile app ecosystem are important to Apple’s bottom line, why would Apple do this?

There are two main reasons:

- The public cares more about data privacy than ever before, so being proactive about digital privacy is a marketing differentiator.

- Laws like the European Union’s GDPR and California’s CPRA are redefining consent around data in the digital era, and Apple is adapting accordingly.

To be clear: this is a good thing. Users have more control over who is using their data, when, and why, which is something that has been abused for decades by internet companies.

So while the growing pains will be difficult, this will pave the way for new advertising technologies and formats that incentivize users to proactively volunteer their data in return for value (e.g. opt-in value exchange ads).

The iOS 14.5 Timeline — What To Expect and When

Even though the data opt-in changes were announced in June 2020, Apple decided to delay that change to give advertisers a chance to get ahead.

As of this writing, iOS 14.5, the version that will incorporate these IDFA changes, is currently available in beta to developers, and the mass consumer rollout is expected sometime this month or next month.

This means that all of the fears and predictions of what this will do to the market will be tested shortly.

How iOS 14.5 and IDFA Will Affect Your Marketing Strategy

The main impact of iOS 14.5 is that conversion tracking will be less accurate, and the granularity of your attribution will suffer.

Without getting too technical, the solution provided by Apple to mitigate the damage of these IDFA changes is to port over to what’s known as the SKAdNetwork, which is an API solution for app activity tracking that is completely user anonymous.

Here’s the difference between that, which will be advertising’s new normal, and what IDFA used to give us.

Here’s what you can still expect to have in a post-iOS 14.5 world[*]:

- Click-through attribution for ads displayed in mobile apps.

- Publisher ID of the publishing app.

- Campaign ID which can be used to code information IDs such as campaign, creative, and placement.

- First time install vs. redownload information.

- Conversion values that allow basic post-install tracking. This helps with analyzing user quality.

- Apple’s cryptographic, unforgeable verification of the attribution and parameters – meaning anyone can verify that an install really happened while still respecting user privacy.

- Still generally accurate and fraud-free attribution.

And here’s what we’ve lost:

- No more view-through attribution. Everything will have to be triggered by a click.

- No more click-through attribution for ads displayed in browser, email campaigns, or any other medium apart from native ads.

- Real-time data. Everything will be set to a 24-48 hour delay to protect privacy.

- No user-level data.

- No more small campaign and publisher data. You must exceed a threshold before Apple reports some conversion information.

- No deep linking and populated long-term cohort statistics like customer lifetime value (LTV).

With that in mind, here are some thoughts and strategies you can use to keep your advertising effective in 2021 and beyond.

How Can Marketers Mitigate the Impact of iOS 14.5?

It’s not all doom and gloom for advertisers. Yes, things will be a bit different from now on, but that doesn’t mean effective digital advertising is gone for good. Start here to stay on top of the changes:

1. Update your SDK to support the SKAdNetwork.

If you haven’t already, get your developers to update your SDK to support Apple’s new SKAdNetwork solution and then verify your attribution across each channel.

For example, take the week after your SDK was updated and verify that the number of installs reported from your Facebook Ads match up to the number of installs you’re seeing being reported in the App Store developer console or your preferred analytics provider.

This gets more complicated the more channels you’re on, but the point is to systematically verify all of your advertising channels’ reporting.

2. Customize the “opt-in” prompt text on your app.

Instead of using cold language like, “Allow Facebook to track your activity across other companies’ apps and websites?”, you could say something like, “Help keep our app free by allowing better ads to be delivered to you with data tracking” or something similar.

3. Ask for IDFA consent after the install.

As long as you ask before you start tracking IDFAs, you don’t have to do it before the install.

Asking before the install could reduce conversion rates, so getting your developers to delay the prompt is a worthwhile A/B test. This also gives you more time in the app to explain how that data will be used.

4. Prioritize first party data.

The more user privacy is championed, the more old-fashioned advertising data’s value will increase — at least until a new type of internet is created.

Email addresses, phone numbers, and other forms of first party data that you can rely on to reach customers directly will become more important as interruptive advertising gets more difficult.

To mitigate the damage of iOS 14.5, try shifting your budgets to use more permission marketing to gather FPD instead of leaning more heavily on interruptive strategies.

5. Tie big-picture data back to individual ad channels.

Take the time to develop the most accurate estimates of “revenue per install”, “customer lifetime value”, and other big-picture metrics, and then use that as a rough estimation of your channels’ effectiveness.

For example, if you know you get around $2 in revenue per install on Apple Search, then you can use that as your floor cost per install when advertising.

6. Accept that things won’t be as accurate, and that’s okay.

You’re not alone in the scramble. Take everything one step and one channel at a time, and reevaluate each step of the way.

As time goes on, technology will get better, so just ride this wave for now!

The Future of IDFA and the Modern Digital Advertising Ecosystem

It’s clear that as sweeping user privacy laws continue to emerge, data privacy products gain market share, and breaches become more common, the protection of user privacy in the zeitgeist is here to stay, and that’s fantastic news.

Yes, it will make advertising more difficult, but that is only temporary. Today’s advertising ecosystem is broken, anyway. Click fraud is rampant, users are served ill-matched ads, and ad blockers are more popular than ever. Plus, attribution has never been flawless.

All of this begs the questions: what if there was an alternative way to approach advertising altogether? Is the system we have the best solution?

A whole new internet.

It turns out, no. There is a much better way to structure the entire digital advertising ecosystem, and we’re building it.

By compensating users directly for opting in to share their data and engage with advertisers, we can incentivize users to share their data in a transparent way, which ultimately builds brand trust and loyalty.

Moreover, advertisers improve conversion rates because the users they reach will be opting in and demonstrating genuine interest in the ads they deliver.

The next generation of the web will usher in this new form of “win-win” advertising. Instead of a zero-sum game, an evolved advertising model will emerge, whereby users can derive financial value from the enormous asset that is their personal data, and advertisers can build long-term relationships.

See how we’re revolutionizing the advertising ecosystem.

California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) Explained

Most of us don’t think about it often, but data is constantly working behind the scenes. Every video we watch, website we view, and article we read is collecting numerous points of data on our behavior and reporting it to its owners.

Any free service you use is packaging up, sharing, or selling your data to a variety of sources, and most of the time we haven’t the slightest idea what data is being sold and to whom it’s being sold to.

Plus, any personal information like credit card numbers, addresses, and phone numbers we enter online is being stored somewhere in the cloud — at risk of being compromised in the next inevitable breach.

After a mostly unburdened twenty years of corporate internet domination, consumers and their elected officials are starting to push back against the existing internet’s ecosystem and its abuse of privacy. The EU’s GDPR represented the first major piece of modern consumer privacy law, and countries and states around the world have started to look to it as a model for their own rights.

In the United States, California has been leading the charge, previously passing the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and now the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), also known as CCPA 2.0, in November of 2020.

The CCPA was a landmark piece of data privacy legislation that went into effect in 2020, and the CPRA is seen as an extension and bolstering of that law. It was widely disputed but seen as a victory by privacy advocates such as Consumer Watchdog and Andrew Yang.

So what is the CPRA and why is it important?

Let’s figure that out.

What Is the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA)?

The CPRA refers to the California Privacy Rights Act, a data privacy law passed with 56.2% of the vote in November 2020. You can view the entire text here.

Known as “CCPA 2.0,” the CPRA strengthens, extends, and alters the CCPA. The CCPA was criticized for a litany of reasons, including having vague expectations, inadequate enforcement, and not providing enough rights, and the CPRA was designed to speak to each of those issues and more.

Specifically, the CPRA introduces new consumer privacy rights, alters some key definitions in the CCPA, puts tougher fines in place for minorities, establishes an official enforcement agency, and much more.

When Does the CPRA Go Into Effect?

Now that the CPRA has officially passed, everything is in motion. Here are the key dates you need to know:

- January 1, 2021 – The CPRA went live, which in effect stopped any conflicting privacy legislation.

- January 1, 2022 – The 12-month “lookback” for any collected data begins. In other words, this is the beginning of when businesses can be held accountable for violating the CPRA.

- January 1, 2023 – CPRA goes live and all exemptions expire — opening up everyone to full regulation.

- July 1, 2023 – CPRA becomes fully enforceable by the CPPA (the organization created to enforce the CPRA).

Note: Even though the official enforcement date isn’t until July 1st, 2023, your data practices are open to scrutiny starting January 1st, 2022.

A Brief Summary of the CPRA’s 6 Biggest Changes

Here’s a rundown of the most important additions and changes the CPRA introduced to the CCPA:

1. Established the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA)

One of the biggest criticisms of the CCPA was how enforcement worked, and leaving the responsibility to the attorney general’s office was clearly not going to work. To fix this, the CPRA created an agency with the explicit purpose of regulating and enforcing the CCPA and CPRA. They will be handling the enforcement, fines, and communication with non-compliant businesses.

2. Created New and Modified Existing Consumer Rights

The CPRA added two new rights to the CCPA — the right to rectification (or correction) and the right to restriction. This means that consumers have the right to have false information fixed and that consumers have the right to restrict how business can use their sensitive data. It also expanded rights around data portability, data exclusivity, and many others.

3. Distinguished Personal Data Into Separate Classes — Standard and Sensitive

The CPRA stipulates that all data are not equal. Social security numbers are different from email addresses in terms of value, for example. With this distinction in mind, the CPRA created different rules and potential fines for each. These rules include stricter disclosure requirements and limitations on how the data can be used.

4. Made Violations Involving the Data of Kids and Minors a Lot More Severe

Parents didn’t feel like the CCPA addressed the privacy concerns of children enough, and the CPRA stepped up to address this by allowing the CPPA to 3x any fine that involves a minor’s data. The law also dictates how consent is managed and allows parents to have more control over their children’s personal information.

5. Forced Companies to Protect Employees — Regardless of Where They Live

In addition to protecting consumers living in California, the CPRA also expanded its protections to any employees and contractors who are working for California companies. This means that any of the rights in the CCPA and the CPRA are enforceable across state lines when they involve employees and contractors.

6. Changed What Kinds of Businesses Are Subject to Scrutiny

The CPRA expanded the law’s scope in some categories and relaxed it in others. For example, small and mid-sized businesses are now exempt when buying, selling, receiving, or sharing data up to 100K consumers or households (assuming they don’t qualify for other categories), but the CPRA made businesses who make at least 50% of their revenue from sharing data eligible — regardless of how much revenue they make.

Let’s look at that a bit more.

Who Does the CPRA Apply To?

The CPRA now applies to:

- Any business that has more than $25+ million in annual revenue.

- Any business that shares, sells, or buys the personal information of 100k+ consumers or households.

- Any business that gets at least 50% of its annual revenue from selling or sharing consumer personal information.

These categories apply to any company that does business within California. If you have users or sell products to California but are headquartered in Miami, you still have to comply.

Why Is the CPRA Important?

The impact of the CCPA and the CPRA will be felt for decades. California is the first major state to pass a set of data laws this comprehensive, and the successes and mistakes they make along the way will be watched carefully by other states across the country. The CPRA could also represent the second step in paving the way for federal consumer data regulation in the future.

The CPRA also forces other amendments to be consistent with the CPRA. In other words, if a county or city decides to pass a law that violates the CPRA, consumers, employees, and contractors could sue based on the CPRA’s protection. This further solidifies the CPRA in the world of law.

And more broadly, the CPRA is another major victory in the world of user privacy. Laws are rarely perfect, but it does represent the second step in a shift toward a more consumer-centric internet ecosystem.

Criticisms of the CPRA

There are common criticisms from larger businesses and corporations that you would expect — namely that the law will be too cumbersome on small businesses, cripple crucial data pipelines, and harm the overall consumer experience, but the more compelling criticisms come from privacy advocates.

The ACLU, for example, came out with a surprising attack against the CPRA labeling it as a missed opportunity [*]. Other critics point out that because the CPRA is fundamentally “opt-out” instead of “opt-in,” it opens the gate for companies to charge more for services that use less data — effectively creating an inequality where lower-income users will be forced to give up their data more often.

The CPRA has also been criticized for not allowing users to sue rule-breaking companies outside of special cases like breaches — only the CPPA has the authority to enforce fines. That being said, the CPRA did give the CPPA the authority to update the CPRA according to how the law handles itself in practice, so we can expect some adjustments that may speak to these issues later on.

What Are the Fines and Consequences of Violating the CPRA?

The CPRA is enforced via its new agency, the CPPA. It is the sole purpose of the agency to enforce the CPRA/CCPA and respond to complaints/hold non-compliant businesses accountable, and the CPRA can also be enforced via data breach lawsuits on behalf of consumers.

The fines for non-compliant businesses can vary widely in amount and are based on two main categories: fines that come into play when a consumer sues a company for a breach and when the CPPA fines a company directly.

For the first category, the fines are defined by these three criteria:

(A) To recover damages in an amount not less than one hundred dollars ($100) and not greater than seven hundred and fifty ($750) per consumer per incident or actual damages, whichever is greater.

(B) Injunctive or declaratory relief.

(C) Any other relief the court deems proper.

In other words, the fines will usually be stackable amounts of $100-$750. This can add up quickly when thousands of customers or incidents are involved.

For other fines, the agency has a lot of freedom:

(2) In assessing the amount of statutory damages, the court shall consider any one or more of the relevant circumstances presented by any of the parties to the case, including, but not limited to, the nature and seriousness of the misconduct, the number of violations, the persistence of the misconduct, the length of time over which the misconduct occurred, the willfulness of the defendant’s misconduct, and the defendant’s assets, liabilities, and net worth.

In other words, whatever the agency feels is appropriate based on the unique case. This is purposely broad.

How Do You Comply With CPRA?

Complying with the CPRA means continuing and expanding the efforts you are making to comply with the CCPA. This includes having clear ways for users to opt-out of data collection, making it easy for users to transfer or change their data, and being proactive about your approach to user privacy.

Similar to the world of PCI Compliance in payment processing, complying with CPRA isn’t a one-and-done deal. Regulators are looking for consistent effort — an internal focus on protecting user rights. This is something that must be a process within your business, and the more thorough you are with that process, the less likely you are to be fined, or in the case of a fine, the less severe it may be. Demonstrating authentic effort is important.

You can structure that effort across three broad categories, similar to how companies in the EU are approaching GDPR. Those categories are:

1. Data Minimization

Data minimization means collecting the bare minimum amount of data needed to fulfill your business’s needs. It’s an active effort against “data bloat,” which unnecessarily makes data breaches more harmful. “Only collect what you need” is the mantra here.

2. Purpose Limitation

Once you collect someone’s personal information, you can only use it to the extent to which the user agreed. If you have been using a particular data set collected with consent for a period of time and want to use it in a different capacity (such as sharing or selling), you must be able to show that users consented to that secondary use as well.

3. Response to Requests and Active Engagement With Privacy Concerns

At its heart, the CPRA is trying to protect user privacy by making data management easier and more transparent for consumers. Businesses should be building systems and processes to make opting in and out of data collection and use more simple.

Phrases like “Do not use my personal information” should be clearly represented on homepages, there should be customer service resources allocated to data management, and resources telling consumers exactly how and why you use what data should exist.

If you work toward these three categories, then you’ll be well on your way.

For a more detailed rundown on how to begin preparing for CPRA’s January 1st, 2022 lookback period, go here.

The Bottom Line on CPRA

If you operate in California in any capacity and fall into one of the three categories mentioned above or plan on growing into one of those categories eventually, you need to be proactive about CPRA.

CPRA and its sister law the CCPA represent a fundamental shift in California’s approach to consumer data and will force businesses to take a hard look at how they collect, protect, and use consumer data.

The best plan is to have a plan, and business owners must demonstrate an active, early, and well-prepared approach to consumer privacy as defined by the CPRA and CCPA.

The World of Permissioned Data

The term zero-party data bubbled up over a year ago. It has the following meaning:

Zero-party data is personal data that a customer deliberately and proactively shares with a brand or a retailer.

Long before the term zero-party data was invented, we referred to such data as permissioned data at Permission. There’s also the term “declared data,” which may confuse the picture — that’s data acquired by such activity as consumer surveys. It is also permissioned data or zero-party data. But let’s not be confounded by the terminology; beneath it all lies an important development in the world of advertising and marketing.

Businesses are beginning to recognize that many individuals are aware that they own their personal data and they are eager to put it to good use. There are many reasons why this has come to pass: because of government regulation, because of outrage at the exploitation of personal data by some vendors, but most of all, it has become clear that personal data has significant value.

Just so we are clear about how this idea emerged, let us quickly describe first party data, second party data, and third party data.

- First Party Data. This is the data that a business gathers directly from its interactions with its audience, usually via its website, or possibly by emails, records of conversations, and any other direct interaction with either its customers or prospects. The important point to note is that until quite recently, first-party data was the highest quality data a business could collect concerning its customers and prospects. Unless it is regularly renewed, it gradually ages.

- Second Party Data. This is no more nor less than second-hand first-party data. It’s the data an organization collects from its audience that it sells directly to another company. Second-party data is likely to be of lower quality than first-party data because, by the time you get your hands on it, it has aged and because you will inevitably be less aware of its context than the company providing it.

- Third Party Data. This is data you can purchase from data brokers and data aggregators. The source companies did not originally collect the data (as first-party data) but aggregated it from multiple sources. Some of the data may be obtained from public sources, government records, social network profiles, and so on. Some of it may come from purchased first-party data. Some may even come from hacker data. Naturally, the quality of the data will vary according to the methods and diligence of the aggregator. In general, item for item, it is likely to be relatively low-quality data.

The Emergence of Permissioned Data

It was against the landscape of these three types of differently-sourced data that the term, zero-party data, first emerged. It was invented by the analyst company Forrester. In the wake of GDPR legislation in the EU, Forrester realized that there was another category of data that did not fit into the first, second, and third-party data categories. And it was important because it was high-quality data.

Because we at Permission had been pursuing a business model based on the productive use of personal data more than a year before GDPR came into force, we had our own ideas about personal data and our own term for it. We called it permissioned data. In our view, permissioned data is personal data that individuals are willing to share with other parties.

There can be a variety of reasons for wishing to share personal data. One obvious example is medical data. People will obviously want to share their personal health data with healthcare organizations. They may want to share their employment data and educational data with potential employers. They may want to share financial records with financial service companies.

And, of course, they may want to be able to share that data in contexts where they can be rewarded for its use. That’s what Permission.io is about and that’s also what Forrester was talking about with Zero-party data.

The Quality of Permissioned Data

Permissioned data is data that individuals own and manage and make available directly. It is high quality for several reasons:

1. It is likely to be up-to-date.

If permissioned data is well managed it will be more up-to-date than first, second, and third party data. Such data was always captured some time ago, possibly quite a while ago. Permissioned data is current data.

The reality of data is that it changes. Addresses change, qualifications change, jobs change, financial status changes, marital status changes, and preferences change. When you think about it, most data is akin to a photograph. Assuming it has not been corrupted, it gives you information that was true at a particular point in time and may no longer be true.

2. It is the prime source.

Regulations are making it increasingly costly to store personal data. You only need to study the EU’s GDPR to realize how onerous storing personal data can be. The data owner has:

- The right of consent

- The right to access the data

- The right to change data

- The right to complain

- The right to erasure

- The right to portability

The point is that if you’re going to store personal data, then you will need systems and software procedures that enable you to accommodate the rights of the data owner.

You will also need a Data Protection Officer. The reason is simple, the EU insists that you appoint one. And by the way, if you violate an EU citizen’s data rights, the fines are steep — up to 4% of your annual revenue (this is not a misprint).

Doesn’t it make a lot more sense to simply rent the personal data you’d like to use, by arrangement with its owner?

Now you may be thinking, “well I don’t deal with EU citizens.” And that may be the case, but if that’s what you think, make sure of it. Because if you hold the data of even one EU citizen, then these rules apply. And if you don’t, but one suddenly gets into your system, then these rules apply. And these rules apply to all organizations in the world, irrespective of jurisdiction.

And, also, you probably need to watch out for your local data regulations too, no matter where your company is based, because the global trend is for governments to increase the regulation of data. The smart move may be to evade those laws by letting the data owner put in all the effort.

3. It is accurate and comprehensive.

Permissioned data is likely to be more accurate. This is partly because it is the prime source and, hence, when you get hold of it, either it has never been copied (because you are using source data directly) or it has been copied just once, temporarily into your analytics system.

Permissioned data is likely to be more coherent in the sense that the data is organized and there is nothing ambiguous about its meaning. Because, at the moment, very few people directly manage their own data, the quality of permissioned personal data will improve over time. Indeed, once data owners get into the habit of curating their own data, they will have a growing incentive to make it as comprehensive as possible. In making this point we are, to a certain extent anticipating the way things will be, but we have little doubt where this trend is heading.

Bear in mind that there are different categories of data:

- Curated data: Information, including credential data, that the data owner naturally assembles from their activities.

- Declared data: Information knowingly provided by a user through surveys or online forms. Some of this will simply be user opinion and it is well known that user behavior does not necessarily align with stated user opinion. Nevertheless, what a user thinks is useful information and matters. Increasingly users will always retain such data.

- Aggregated data: Data aggregates in which user data may participate. For example a collection of the personal data of all the people who support a particular sports team.

- Inferred data: Data logically inferred from a user’s personal data. For example, certain user preferences can be known by employing correlation algorithms to user data.

- Behavior data: Data gleaned from tracking user activity in any context, particularly online, to determine preferences.

Permissioned data will be better in all these contexts. Not only is it likely to be more accurate, but it will also be more coherent — less likely to contain puzzling contradictions.

4. It will improve with time.

The final important point is that permissioned data will get better over time. On the one hand, once data owners get into the habit of permissioning their data, they will also cease to let their data be copied, legally or otherwise. And once they realize that it is possible to monetize their data most people will try to maximize its value, which will mean accumulating as much of it as they can.

The sources of first, second, and third party data will, at some point, begin to wither on the vine.

Data Evolution

Recent activity, by Apple in providing its iPhone and iPad users the ability to opt-out of sharing IDFAs (IDs for advertising) and by most of the browser software companies in sidelining third-party cookies to the point where they will become obsolete, has put marketers in an awkward position. You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the winds blow here. Third-party data is going to become harder to accumulate.

As this corner of the market runs into problems, at the other end of the spectrum the evolution of permissioned data has only just begun. The point is this: permissioned data is in its infancy.

Yes, of course, it will prove extremely useful to brands and retailers and it will soon drive a new and exciting advertising platform. Advertisers will enjoy higher quality data than they’ve ever previously known and the ROI on their advertising will improve, perhaps dramatically.

And by the way, did I mention that once you have direct interactions between consumers and advertisers, all of those bots which plague other advertising markets will be locked out? If we do this right, the hackers and the scammers will melt away like snow on the water.

We should see this for what it is, an evolution of the market for personal data. Once individuals control their data, innovators will naturally enter into the market with new ideas about how the data owners can profit most.

This is not the same data that has been collected in a fragmented way by those who deal in first, second, and third party data, this is a data resource assembled from an alliance of the data owners. It is higher quality, it is far more coherent, and it will prove to be far more useful, not just to advertisers and brands, but to all organizations that interact with individuals.

Robinhood: A Lesson In Transparency For Brands

We have all been enthralled by the stories coming out about GameStop, WallStreetBets, and Robinhood. This wild adventure offers a powerful lesson for all brands: Be transparent about the customer data you collect and how you use it.

Robinhood, a one time darling of the fintech world, is a company whose motives some are now questioning. And at the heart of it is a parable about data, transparency, and trust.

Brands can learn a lot from the Robinhood story, but first, let’s get our facts about the company straight.

Robinhood made big waves when it first came out because of its enticing offer of free trading. Competing brokers were charging $5 to $10 per trade. This quickly allowed Robinhood to capture millions of new customers nationwide and grow rapidly over the course of just a few years. They made laudable and bold claims such as, “we believe the financial system should be built to work for everyone.” Those claims would quickly be tested.

When people first heard of Robinhood’s no-fee model, they were sceptical, and rightly so. Everyone asked, “What’s the catch?”

That question came to a head in December of 2020 when the SEC fined Robinhood $65 million for “misleading customers about revenue sources and failing to satisfy duty of best execution.” They declared that Robinhood made misleading statements and omissions in customer communications about its largest revenue source when describing how it made money. And despite their previous claims, their customers’ orders were executed at prices that were inferior to other brokers. The Better Business Bureau gave the company a failing grade in matters of transparency and trustworthiness.

Robinhood achieved its no-fee trade model by utilising a practice known as PFOF (Payment For Order Flow). This means the company was selling its customers’ trade data to market makers and high-frequency traders, who then used that data to fill orders at unusually high prices. And this was Robinhood’s largest source of revenue, a fact that the company did not disclose on their FAQ page. Customers never got a clear view of what the best price for a trade was, whether their order was executed at that best price, or how much profit was captured by Robinhood and their market maker in the process.

Robinhood essentially sold overpriced stocks to their customers while selling the data of their customers to Wall Street for their own profit — and they failed to disclose that information to the public. The company placed itself in a conflict of interest as they attempted to simultaneously serve their customers and the Wall Street firms that pay them.

The SEC ruling was a setback for Robinhood, but it was one the company could have shaken off.But then came the Gamestop short squeeze.

Robinhood suddenly found itself in the middle of a war between retail investors and Wall Street. And just when the drama hit a fever pitch, they halted the trading of GameStop stock. Robinhood likely had legitimate operational reasons for this decision, and the facts seem to support that. But, it hardly matters.

Robinhood’s practice of selling customer trade data without informing the customer had already eroded some trust in the company – many assumed that they were siding with their Wall Street partners when they restricted trading of GME.

If Robinhood had originally been more transparent about how they used customer data, the public would have slowed their rush to judgment as the company halted the GameStop frenzy. When the company most needed the benefit of the doubt, many remained sceptical of their motives.

There is a lesson in all of this: Using and profiting from your customer’s data without their informed permission may still be a standard business practice, but it won’t be for long. The public is not going to accept it anymore.

If your company isn’t completely transparent about what customer data you use, take a moment to consider how that could backfire on you. If your brand isn’t specifically asking for permission to use all of the customer data that you currently use, it’s time to reconsider that approach.

Trust is paramount when it comes to relationships between brands and consumers, and transparency is key to that. Respect their data, respect their choices and always be upfront and honest with them.

You never know when your company’s ‘GameStop moment’ might come. If you haven’t fully earned your customers’ trust, they will be reluctant to give you the benefit of the doubt.

Don’t let your brand take a hit.Be transparent.Ask permission.Build trust.And if you need help with that, just ask us. It’s what we do best.

SMS Marketing: Uses, Examples, & Best Practices

Thinking about adding SMS marketing to your mix? You’re in the right place.

SMS or text message marketing is a powerful tool that can be a great addition to your funnel, but you need to be careful with how you use it. Bombarding people with messages on their personal devices is a sure way to sour your customer relationships.

We’re going to give you an overview of what SMS marketing is, talk about some of the best ways to start using SMS marketing and give you a few recommendations on how to get started.

By the end of this blog, you’ll have everything you need to know to add SMS marketing to your marketing mix.

Onward and upward.

What Is SMS Marketing?

SMS or text message marketing is when companies and brands use phone numbers supplied by customers to reach out with product, sales, and content messages.

Anytime a customer offers a phone number and “opts-in” to receive text messages, they and the brand are participating in SMS marketing. SMS marketing is a popular way to deliver appointment-based messages, run contest giveaways, and offer automatic transactional messages.

Is SMS Marketing Effective?

Like most marketing tools, oftentimes it’s not the medium or channel that is or isn’t effective, it’s how good you are at matching your product and message to your customer’s needs or desires. SMS marketing can be incredibly effective, but it can also turn off your customers — the same way a good TV ad can make or break your business.

What SMS marketing is known for is its open rate — almost everyone reads every text that comes to their phone, with some reports estimating that 98% of all texts get read.

That’s what makes this such a powerful tool, but that power can swing both ways. People have less patience for ads in such a personal space, so you have to be timely and relevant or risk being blocked or unsubscribed from.

When to Use SMS Marketing

The way a restaurant chain uses SMS marketing will be different compared to how a SaaS company or entertainment company uses SMS marketing. Its capabilities and uses are broad, but here are a few common ways people use SMS marketing to get the ball rolling:

- Contests or giveaways. SMS marketing is a great way to drop links and pull customers into exciting contests.

- Flash sales. It’s awesome for limited or rotating inventory businesses, both offline and online.

- Booking confirmations. Any appointment or consultation-based businesses can benefit from auto-confirmations and reminders.

- Customer order/delivery updates. Most of us are familiar with Amazon’s SMS marketing letting us know when our order has arrived or if it’s delayed. How can you emulate this information-based tactic in your own business?

- Internal messaging at large companies. SMS marketing isn’t only about external communication. When a company is large enough, sometimes email isn’t fast or thorough enough. If the office is closed or a big announcement needs to be made, texting everyone can be the best route to ensure they see it.

- Content updates. This works best for companies who make their money through content, but you could announce a new video, podcast, or blog through text if the audience is devoted enough and is looking forward to hearing from you, e.g. a podcast that releases every two weeks and lets listeners know that a new episode is up.

- For meet-and-greets. A clever SMS marketing tactic is to use texting for meet-ups or VIP events. This allows you to capture the phone number for future marketing and offers a simple experience for customers. For example, if you were playing a show or hosting a conference, you could have a “text this number” to a free meet and greet giveaway after the show. You could also use this functionality to message details to VIP purchasers and follow up with them with photos or extra content after the event.

Benefits of SMS Marketing

The benefits you can get from SMS marketing will depend entirely on your industry and how you choose to build it into your funnel, but here are some of the ways businesses benefit from implementing SMS marketing.

1. Can Decrease Appointment No-Shows

Appointment confirmations and reminders via text will increase the number of people who show up on time to your appointments.

2. Can Increase Local Foot Traffic to Businesses

SMS marketing works really well with localized and timely discounts. An easy example of this is a holiday announcement. Say you were a local donut shop and had a limited release donut for Father’s Day. Let’s say it’s a yellow and pink Simpsons donut called the Homer. You could send a text out to everyone who lives nearby with something that says:

Happy Father’s Day from What’s Up Dough! We are celebrating with a ONE DAY limited Homer Simpson Donut — key-lime pink icing with sweet cream. YUM. Drop by now! We usually sell out by 12! Much love.

A marketing move like that is bound to increase foot traffic in your business, and data backs up that assumption: Dynmark quoted that 29 percent of SMS marketing recipients click on links in SMS messages they receive, and 47 percent of those go on to make a purchase. That’s a conversion rate worth paying attention to.

3. Gives Incentives to Loyal Customers

Similarly, you could segment your customers by loyalty, customer longevity, etc., and reward those customers. You can make this fun by saying something like:

Don’t let anyone say you aren’t consistent — did you know that you are part of an elite group of coffee lovers who have ordered the exact same drink: cold brew with oat milk for the last 2 years? Wow. To reward that dedication, we’re giving you a free one — on the house! Just drop by and show this text!

This is a great example of how to make these texts more personal and interesting.

4. Gives an Outlet to Send Critical Information

You need to be careful not to overuse texting, but if your hours have changed significantly or if you’ve had another substantial update like a new product, service, or location, then SMS text messages are a perfect channel to deliver that information.

5. Provides Direct Service to Customers

If you set up your phone line to be two-way, you can also use texting as a direct support line and enable your customer service professionals to be even more hands-on.

How to Start Using SMS or Text Message Marketing

There is no shortage of SMS marketing software, and SMS marketing generally falls into two camps: text message marketing campaigns and transactional auto-responders.

Most official SMS marketing services give you the option to do both, but some shopping SaaS companies allow you to send auto-text confirmations, etc. but don’t allow you to be more granular. Look at your existing stack and see if a service you’re already using allows you to do SMS marketing.

If not, then consider the following options.

1. Twilio

Twilio has been at the top of the pack for multi-channel messaging for years, and their integrations, developer community, and customization features are the real deal.

Key Features

- Interest-based texting and communication

- Works hand-in-hand with other messaging platforms like Facebook Messenger

- Serves as an all-in-one solution for customer communication

Ideal for

Enterprise or established businesses with complex interest messaging and channel needs.

Pricing

They bill entirely off of messaging — whether that’s phone calls, texts, video chats, etc. The rates change for each, and they also offer bulk pricing.

2. EZ Texting

EZ Texting has been a power player in SMS marketing since 2004. Their partnerships, integrations, and resources make it worth looking over.

Key Features

- Keyword-based texting lists

- Drip campaigns

- Recurring messages

- Sign-up forms

- Reminders

- Picture capabilities

- 1-on-1 chat functionality

- Link shorteners

- Personalization

Ideal for

Companies that already have a CRM, customer database, etc., and are solely looking to add text messaging marketing to their business.

Pricing

Starts at $19/month but scales up according to reach and frequency of messages. Rates average out to around $0.04 per message after you exceed your plan’s message ceiling.

3. ActiveCampaign

ActiveCampaign is one of my favorite CRMs and is always releasing new features around email marketing, SMS marketing, and contact database management.

Key Features

- Text-based automation

- Appointment Reminders

- Builds seamlessly into the CRM and email marketing platforms

- Can easily combine SMS automation with email automation and trigger based on behavior

- Fantastic service and onboarding

Ideal for

Companies that haven’t settled on a CRM and want to centralize all of their marketing software. Or, for companies who want to have a lot of freedom over how they build their automation across multiple channels.

Pricing

SMS Marketing starts at a base of $49/month and scales up with the number of contacts and messages you send out.

4. Sendinblue

Sendinblue is another complete marketing SaaS service with email marketing at its heart. If you’re looking for an email marketing service and want text capabilities included, then they could be for you. If you’re already happy with your email marketing system, then I’d go elsewhere.

Key Features

- Interacts directly with their CRM

- Time and behavior-based text messaging

- Personalization

- Reporting and Analytics

- Transactional Emails

Ideal for

Similar to ActiveCampaign, Sendinblue is an all-in-one marketing software aimed at consolidating your contact management and marketing automation. It’s not nearly as complex as something like Twilio and is a better fit for smaller businesses. Take a look at each platform’s integrations to see what the best fit is for you.

Pricing

Their automation features start at around $65/month and scale up according to email and text volume.

—

Most of these companies have a litany of integrations that your existing marketing stack can plug into, so make sure that whatever company you choose will play nicely with your stack, otherwise, you will have a harder time using it to its full potential.

It’s also worth noting that most of these companies offer free trials, so it’s a good idea to hop in and see which one you like working in.

Best Practices for SMS Marketing

While SMS marketing is fairly broad, there are definitely ways to do it poorly and even illegally. Here are few best practices to make sure you start off on the right foot.

1. Never send a text to someone who hasn’t explicitly opted in.

Collecting and texting people without their permission is against the law. For the safest and best practice, always have the texting system be opt-in and confirm their subscription in the first text. More on this in the next point.

2. Be aware of text opt-in laws.

According to the Telephone Consumer Protection Act, you have to follow anti-spam policies when conducting SMS marketing. This includes guidelines that say you should:

- Always make it permission-based

- Always provide information on how to opt-out in each exchange

- Always mention your company name

- Disclose any carrier costs

- Never message about sex, hate, alcohol, firearms, or tobacco

3. Only use it in highly specific situations.

Again, texting people is a tool that should not be considered lightly. There is no quicker way to annoy someone than by overloading them with texts. Be smart, timely, and always think about your customer’s perception and experience when using text message marketing.

4. Use personalization and be human.

This is especially important for small businesses. Call your customers by their names, write as if they were coming from someone they know, and try to be as relevant as possible. Relevancy can be related to time (e.g., not sending a coupon about caffeine after 5 PM), being aware of where they are in their customer lifecycle with you, what they purchased last, holidays, etc.

In short, always try to tie each text to as much data as possible.

5. Remember time zones and don’t send during weird hours.

A classic SMS marketing mistake is to send out a slew of texts at 8 AM EST… which would be 5 AM PST. Always make sure you are sending at the appropriate time across time zones.

6. Use geography and event-based thinking.

SMS is really great when you use location and timing to your advantage. For example, if you’re a hot dog stand company with dozens of stands around a football stadium, you could time a text to all of the tipsy fans on your list leaving the stadium and give them a $1 off coupon for a dog.

7. Plug it into your existing funnel.

Look at SMS marketing as another piece of your marketing machine. I like to sketch out my entire funnels from the top down using software like Funnelytics to get the big picture. You want to make sure that each channel you’re using is working with each other, otherwise, you risk annoying your customers with too many messages or with repeat messages and causing damage to your customer experience and reputation.

8. Make each text actionable.

People don’t like to be interrupted for no reason. Make sure there is a clear and obvious benefit to be found within the text you send, and tie that directly to your call-to-action.

The Bottom Line on SMS Text Message Marketing

With the right strategy and preparation, SMS marketing can be a great tool for your business. My advice is to analyze your existing marketing funnel and identify some specific places where you could add SMS marketing in. Once you’ve identified those places, sign up for a service that is most friendly toward your existing and/or ideal tech stack and begin building out your initial campaigns.

Remember. Strategy first — always.

Good luck.

Permission.io is revolutionizing the internet as we know it — we’re handing data ownership back to the people and rewarding individuals for their permission to engage… we want you to be a part of it.

Second Party Data: Definition, Benefits, & Use Cases

In the world of modern marketing, second party data can feel obscure. You may have heard how great it is for audience expansion or new marketing campaigns, but it often feels like there’s a barrier to entry that’s much higher than collecting pixel data on your website (i.e. first-party data) or using databases that allow you to drill down by approximate demographic and psychographic (oftentimes third-party) data.

We’re going to demystify second party data for you and talk through actionable ways you can use and find it for your own company. It’s not for everyone, but if you’re working for a company that is actively scaling or is realizing its existing audiences are going stale, then second party data may be the ticket to your next success.

Before we go into the details on second party data and how to best use it, let’s briefly talk through the three other data types businesses use:

- Zero party data is any consumer-owned data that is given up voluntarily by a consumer to a company in return for some benefit.

- First party data is proprietary data collected by companies directly from their customers.

- Third party data are large data collections gathered by companies who are not the original collectors of that data.

What Is Second Party Data?

Second party data is data collected directly from users by one company and then sold or given to another business. It is often sold in private deals, exchanges, and used by social media and advertising platforms to improve targeting.

Put another way, second party data is first-party data that has been packaged and sold to another business.

Common examples of second party data include purchase behavior data, age and other demographic identifiers gathered from surveys, website cookie information, emails, device data, and user behavior data like login frequency and engagement.

Second party data is most often collected and sold in what are known as second party data marketplaces — if you hear words like data stream, data marketplaces, and private data exchange, those are businesses likely dealing with second party data.

Examples of Second Party Data Exchanges

A few of the more well-established exchanges include:

Second party data has exploded in popularity after GDPR‘s introduction and subsequent hamstringing of third-party data, and without more government intervention there’s no sign of it slowing down.

Modern second party data is reaching a point of sophistication where marketing leaders can effectively clone their existing profitable audiences at scale, and that’s a powerful driver for growth and continued innovation — plus selling data is still the primary revenue channel for most free apps.

Who Uses Second Party Data?

Anyone who has an interest in expanding their customer data information or in selling user information uses second party data. This could be anyone from data engineers, to marketing executives and consultants, to data scientists, to product management teams scoping out a potential market for a new idea.

Is Facebook Considered 2nd Party Data?

Facebook’s pixel, analytics, and demographic tools encompass all four types of data, from zero all the way to third. For example, if you’re using a pixel on your site, then that would be considered first-party data because your unique business is collecting information about your unique customers.

If you created an agreement outside of Facebook to share audiences with another business, and then they shared a custom audience with you that they directly collected, then that would be considered second party data.

The Power of Second Party Data: How Businesses Use It

One of the hardest parts of using second party data is narrowing down your choices — the extent of its capabilities is astounding. Businesses use it for everything from improving their own audience datasets to foster omnichannel marketing to mining interesting datasets for new products.

We’ll cover the broad umbrellas under which many businesses use second party data, but know that this is the shallow end of a very deep pool.

1. To Refine Existing Customer Profiles

The more channels and ways you can reach your customers and prospects, the more fragmented that marketing ecosystem tends to become. Just imagine the number of channels a modern eCommerce business that sells nationally could use:

- Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Pinterest, LinkedIn, and others

- Google Ads

- Email Lists

- Shopify

- Specific Trade Publications

- OTT Marketing

- Traditional Print Ads

- Traditional TV Advertising

- Retargeting Sites like Adroll

Now imagine trying to coordinate a marketing effort between those channels. It gets complicated quickly — especially if you can’t tell if the audience you’re emailing is the same audience that’s getting your display ads on Google, or if the print ads are also reaching the geo-targeted email lists you have. Multiply that by country, state, and city, and you can see how the variables just spiral out of control.

Think of second party data as the flashlight that can illuminate and mend those blind spots — allowing your business to close the data gap and make sure you’re reaching the right platforms at the right time without wasting money by targeting the same customer twice or not efficiently moving them from one segmentation bucket into another.

Second party data marketplaces allow you to upload your own first-party data and combine it with other data sources to “round out” your customer profiles. For example, it could point out that 15,000 of your customers actually use Android devices and aren’t getting your Apple App install ads. Or maybe you realize that 5,000 of your users use a particular fitness app that you aren’t advertising on.

In short, if there’s data you wish you had on your customers, second party data may be the route to get it.

2. To Mine for New Audiences

Another use of second party data is finding new audiences to market to. Let’s say you ran marketing for a national music brand that sold pianos, and you wanted to find more people who would like your product. Wouldn’t it be useful to create an audience of everyone who has ever downloaded an app related to pianos and then use that to create a new remarketing audience? You could create that opportunity by purchasing that data directly from the app owner.

3. To Boost Analytics and Insights

Second party data can be useful for understanding how your existing and potential customers behave. For example, by being able to see what other customer lists similar to yours are paying for a type of product on an annual basis, you can better refine your customer lifetime value and get an idea of how much of the market share you and your competitors are taking.

4. To Generate and Test New Product Ideas

Let’s say you owned a clothing store and were thinking about building an app designed to connect personal stylists with your users for custom outfits. It would be useful to understand what types of people are using similar apps. By purchasing that app data, you could create your buyer personas and build your marketing plan from hard data instead of just guessing.

5. To Improve Segmentation Targeting

Tying in other data sources to your existing stream can dramatically increase your ability to segment your audience. Instead of only typical demographic and channel breakdowns, you could add in additional identifiers like shopping habits (e.g., night shoppers), app users, purchase behaviors, and more.

When employed correctly, this specificity will boost conversion rates, reduce ad waste, and help you scale in a profitable fashion.

6. To Sell Your FPD to Other Companies

Again, any first-party data that is sold or given becomes second party data, and some companies make all of their money this way. Social media companies do this most famously, but anytime you’ve heard of email lists being sold or purchase behavior information being given to complementary businesses, that’s an example of second party data.

Some second party data platforms let you upload your data to their stream, organize your bid prices, and manage your customer relationships all within a convenient dashboard.

7. To Create Lookalike Audiences

A simple way to take advantage of second party data is to work with a data provider to share Lookalike Audiences to your Facebook Advertising Profile. There are rules, but if you’re building a new product or looking for new audiences to reach out to — buying second party data from a relevant source and using it to build Lookalike Audiences can be a great way to start your campaign.

This is just the surface of what second party data can do. It is an incredible resource with the right infrastructure behind you, but getting access to this data at scale can be cumbersome and expensive.

Next, we’ll talk about the most common ways businesses access and sell second party data.

How Businesses Access and Sell Second Party Data

How can you access second party data? Well, that answer is a bit convoluted. Outside of private deals, second party data is notoriously expensive and often requires significant internal tech investments to foster communication at scale. That being said, there are a variety of players entering the market aiming to solve just that by approaching it like an eCommerce business.

Here are the main ways you can collect second party data:

1. Private Deals With Other Companies

The simplest way is to work directly with the company you want to buy from. Contact their CTO or marketing head and see if you can get a call on the books. You’ll know exactly who you’re dealing with, be able to hash out details of the agreement, and are likely to get more hands-on support with this route.

2. 2nd-Party Data eCommerce Platforms

There’s a wave of platforms that are aiming at creating “data streams” that facilitate communication, buying, and selling of second party data. By creating simple ways to sell and buy, having pre-written use contracts, and data integrations, this is likely the future of second party data.

Examples include: Narrative I/O and Lotame.

3. Google, Facebook, or SaaS Companies

A lot of second party data drives key functionality in SaaS, social media, and tech businesses. For example, Google Affinity audiences are an example of second party data. This is data on its users, collected by Google, and then shared with advertisers.

The same goes for Facebook saved audiences. Targeting users by interest, group membership, etc. is data collected by Facebook and made available to you.

Second Party Data: No Longer the Best for Marketers or Consumers

Second party data is incredibly useful. There is no denying that, and it’s still a fantastic tool for segmentation and creating better interest matching between advertisers and consumers.